Introduction

If you’ve used the Cursor code editor’s @codebase feature, you’re probably familiar with how helpful it can be to help your agent understand codebases. Whether you need to find relevant files, trace execution flows, or understand how classes and methods are used, @codebase gathers the necessary context to carry out your task. In this post, we’ll discuss a new tool,

CodeQA

, built using LanceDB, that demonstrates how this functionality might work under the hood.

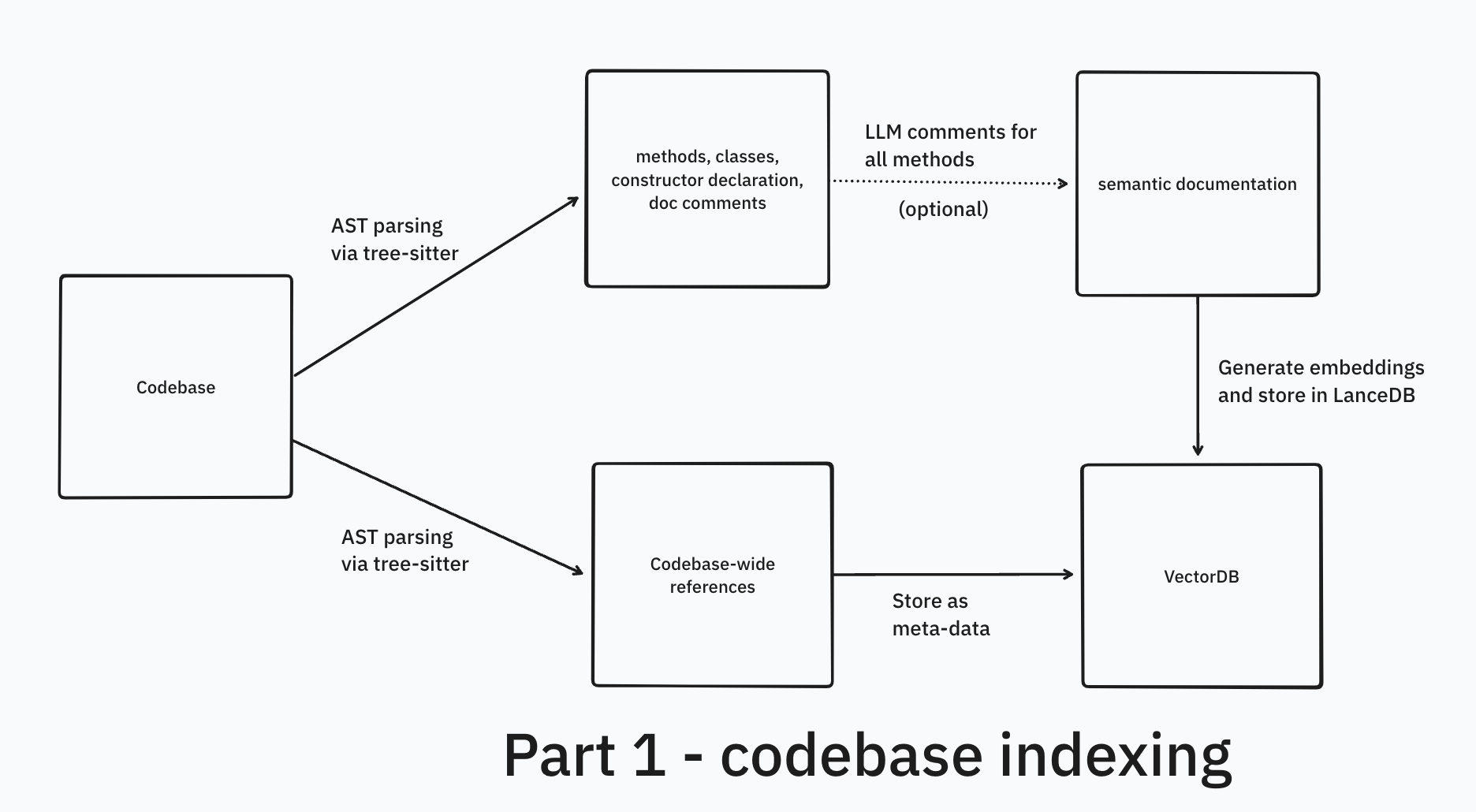

Like you may be used to doing in Cursor, CodeQA can help answer queries that span across your entire codebase, with relevant snippets, file names and references. It supports Java, Python, Rust and Javascript, and can be extended to other languages easily. There are two crucial parts to this – codebase indexing (Part 1) and the retrieval pipeline, discussed in the next post in this series ( Part 2 ). This post is all about codebase indexing with the help of tree-sitter and then generating embeddings.

See a preview video of CodeQA in action here !

What to expect

This post focuses on concepts and the approaches one can take rather than specific implementation details (except some code snippets). We’ll highligh why in-context learning isn’t the best approach for code QA. We’ll also illustrate the limitations of naive semantic code search, and elaborate on the types of chunking that can help improve results. Specifically, we’ll highlight a syntax-level chunking using the tree-sitter library.

Problem statement

The goal is to build an application that will help the user (or agent) understand a codebase and generate accurate code by providing the following capabilities:

- Answer natural language questions about a codebase with accurate, relevant information

- Provide contextual code snippets and analyze code usage patterns, including:

- How specific classes and methods are used

- Details about class constructors and implementations

- Track and utilize code references to:

- Identify where code elements are used across the codebase

- Provide source references for all answers

- Leverage gathered context to assist with code generation and suggestions

Questions can range from simple (single-hop) to complex (multi-hop). Single-hop questions can be answered using information from a single source, while multi-hop questions require the LLM to gather and synthesize information from multiple sources to provide a complete answer.

Examples:

- “What is this git repository about?”

- “How does a particular method work?” → where you may not mention the exact name of method

- “Which methods do xyz things?” → it is supposed to identify the relevant method/class names from your query

- They can be more complex, e.g. “What is the connection between

EncoderClassandDecoderClass?” → The system is supposed to answer by gathering context from multiple sources (multi-hop question answering)

Now that the problem statement is clear, let’s think about how we might implement a solution. LLMs are a great tool to help solve this!

Why can’t GPT-4 answer questions for my codebase?

While GPT-4 was trained on a vast amount of code, it doesn’t know about your specific codebase. It doesn’t know about the classes you’ve defined, the methods you’re using, or the overall purpose of your project.

It can answer general programming questions like “how does useEffect work”, but can’t answer questions about your custom code like “how does generateEmbeddings() work?” because it has never seen your specific implementation that named it that way.

When asked about your specific code base, GPT-4 will either admit it doesn’t know or hallucinate (more likely, the latter) – making up totally plausible, but incorrect, answers.

In-context learning approach

Modern LLMs like Anthropic’s Claude and Google’s Gemini have very large context windows – ranging from 200K tokens in Claude Sonnet to 2M tokens in Gemini Pro. These models excel at learning from context (in-context learning) and can effectively learn patterns and perform specific tasks when provided with examples in the prompt, making them powerful few-shot learners ( source ).

This means you can plug all your code from smaller/medium-sized codebases (i.e., all your side-projects) into Claude Sonnet and even large codebases into the latest Gemini Pro. This way you can ground the LLMs with your codebase context and ask questions. I frequently use the above two for codebase understanding, especially Gemini (it works surprisingly well). Here’s a trick you could use – try changing a github repo’s URL from github -> uithub (replace “g” with “u”). This will render the repo’s structure in a way you can directly copy-paste it into a prompt for an LLM. A tool I use locally sometimes is

code2prompt

.

A quick primer on few-shot learning: You can provide information or examples in the context of the LLM – think, the system prompt or the larger prompt itself. This info can be used as reference or can be used to learn patterns and perform specific tasks.

In-context learning , or ICL, is a method where you provide information to the LLM at inference time, and it’s able to answer your questions even though it wasn’t trained on that context, because it learns patterns or memorizes new information on the fly.

A recent paper titled “In-Context Learning with Long-Context Models: An In-Depth Exploration” shows that LLMs with large context show increased performance when presented thousands of examples. See this tweet thread for more info.

Why ICL is not the best approach

In this section, we’ll elaborate on why ICL may not be the best approach for code QA.

Performance degradation as context window fills up

Pasting a few files as context in Claude Code or Cursor’s chat UI is feasible until things don’t get larger than the context window. As the context window fills up, the model’s code generation and understanding start to degrade. The sooner you overwhelm the LLM, the less likely it would be able to answer your queries or generate useful code.

Cost inefficiency

If you are paying per LLM API call, sending lots of tokens for each session can quickly get expensive.

Time inefficiency

Pasting large codebases into Gemini works but it can get time-consuming in two ways - Gemini takes time to process the initial prompt with all the code, and then response times increase as the context window fills up. It’s good for self-dev purposes.

Poorer UX

From an end-user perspective, it’s not a fair ask to expect the user to copy-paste their entire codebase into the LLM each time they want to answer a question or generate some code.

Relevance Issues

Dumping too much code into context can actually harm the quality of responses. The model might get distracted by irrelevant code sections instead of focusing on the specific parts needed to answer the query.

Towards more relevant context

It’s clear we need to minimize the irrelevant tokens that make their it into the context for the LLM. Recall that our query can be in natural language and may not contain the correct class or method names, due to which exact matches or fuzzy search will not work. To map our query to relevant code symbols (e.g., class names, method names, code blocks), we can leverage semantic search using vector embeddings. In the following sections, we’ll explore how to effectively extract and index code chunks to generate high-quality embeddings.

Embeddings 101 and the importance of structure

If you’re new to this topic, you can refer to this excellent article by Simon Willison for a primer on embeddings.

Understanding embeddings and chunking

Let’s walk through a simple example to understand embeddings and how chunking works. Say we want to find relevant quotes about “ambition” from Paul Graham’s blog posts.

First, let’s look at why we need to break up (or “chunk”) the text. Embedding models can only handle text up to a certain length – usually between 1024 to 8192 tokens. When we have a long piece of text, like this blog post, we need to split it into smaller pieces that fit into the LLM’s context window. This helps us match relevant content while keeping the meaning intact.

Here’s how we typically handle this:

- We break down the text into manageable chunks that:

- are small enough for the embedding model to process

- still make sense when read on their own

- keep enough context to be useful

- Splitting is usually done in the following ways:

- fixed size chunking (splitting into equal-sized pieces)

- split based on number of tokens

- use smart splitters that adapt to the content (like RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter)

To help with this, we can use tools like LangChain or LlamaIndex. These frameworks come with built-in splitters that handle different types of content:

RecursiveCharacterTextSplitterfor general text- Special splitters for markdown

- Splitters that understand the meaning of the text

One important thing to remember is that different kinds of content need different splitting approaches. A blog post, code, and technical documentation each have their own structure - and we need to preserve that structure to get good results from our embedding models.

Here’s the whole process from start to finish:

- Split your content into chunks based on what kind of content it is

- Turn those chunks into embeddings using a model (like

sentence-transformers/bge-en-v1.5) - Save these embeddings in a database or simple CSV file

- Also save the original text and any other useful info

- When someone wants to retrieve via semantic search:

- convert their search into an embedding

- find similar embeddings (using math like dot product or cosine similarity)

- return the matching chunks of text

This understanding of chunking and embeddings is crucial as we move forward to discuss code-specific chunking strategies, where maintaining code structure becomes even more important.

References

Towards a naive semantic search solution

The process works as follows:

- Embed the entire codebase

- User provides a search query

- Convert query to embedding and calculate cosine similarity

- [Semantic code search completes]

- Get top 5 matching code blocks

- Feed the actual code (metadata) into the LLM as context

- LLM generates the answer

We need to figure out how to embed our codebase for best possible semantic search.

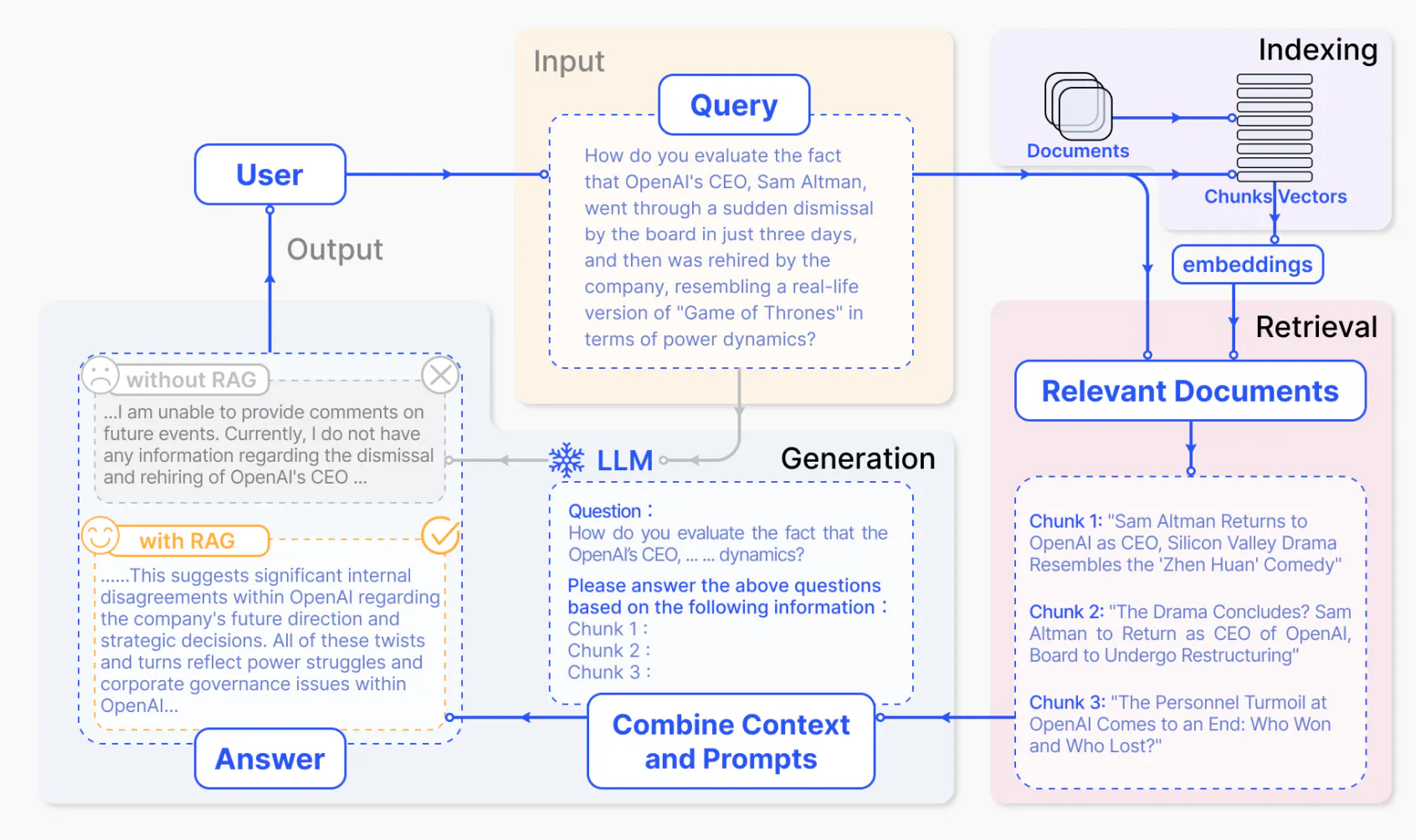

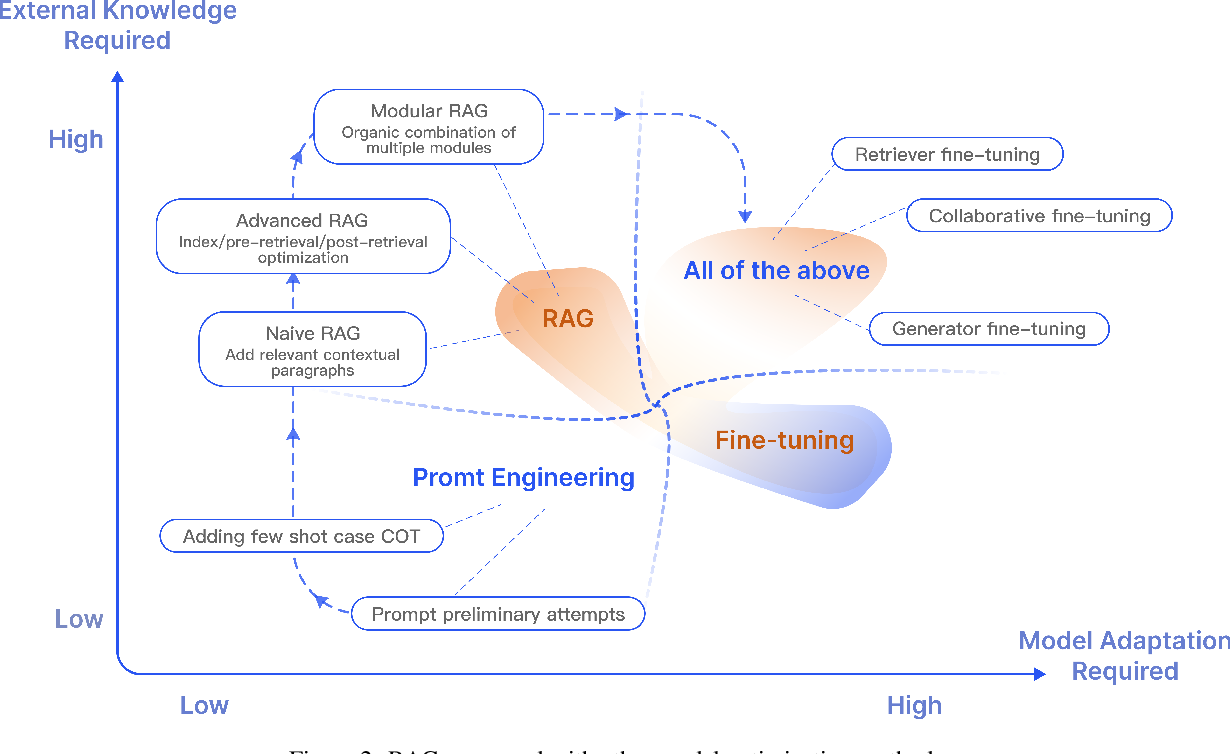

Providing context to LLM via semantic search or other retrieval techniques (could be SQL) to aid it in generation (and avoid hallucination) is called Retrieval Augmented Generation. I recommend reading Hrishi’s three part series on RAG going from basics to somewhat advanced RAG techniques (but first finish reading my post, thanks). My posts are application of part 1 and part 3.

The following images from the paper “ Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey ”.

Chunking a codebase

Chunking blocks of code like we do for text (fixed-token length, paragraph-based, etc.) will not automatically lead to good results. As developers, we intuitively know that code has a specific syntax with meaningful unit and well-defined structure, such as classes, methods, and functions. To effectively process and embed code, we need to maintain its semantic integrity.

The intuition is that the structure that’s inherently present in code would be similar to other code that has a similar structure in the latent space of the embedding. Another factor is that embeddings may have been trained on code snippets, so they might be able to better capture the relationships in the code’s primitives.

During retrieval, entire blocks of methods or at least, references to the blocks, would help a lot, rather than retrieving fragments of a method. We would also like to provide contextual information like references, either for locating the embeddings, or while feeding context into the LLM.

Method/class-level chunking

You can choose to do method-level chunking or class-level chunking. For reference, see the OpenAI cookbook , which extracts all functions from code and embeds them.

Syntax-level chunking

Code presents unique chunking challenges:

- How to handle hierarchical structures?

- How to extract language-specific constructs (constructors, class)?

- How to make it language-agnostic? Different languages have different syntax.

That’s where syntax-level chunking comes in.

- We can parse the code into an abstract syntax tree (AST) representation

- Traverse the AST and extract relevant subtrees or nodes as chunks, such as function declarations, class definitions, entire class code or constructor calls. It allows to extract from varying level of granularity uptill a single variable

- Also possible to get codebase wide references with some implementation

- By leveraging the AST, it’s possible to capture the hierarchical structure and relationships within the code

How to construct the AST?

Python standard library comes with a convenient module, ast. While this may be robust, it’s limited to Python code only. A more language-agnostic solution was needed for CodeQA.

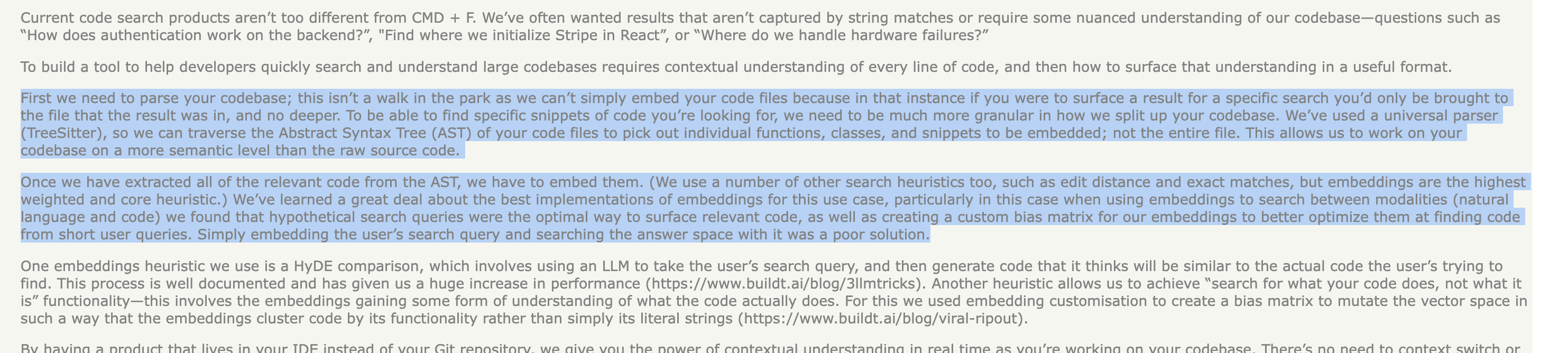

Upon digging deeper - through technical blogs, exploring GitHub repositories, and discussing with friends who work on developer tools, we found that a pattern began to emerge: the term “tree-sitter” kept coming up in these sources.

What made this interesting wasn’t just that we discovered a new term, but realizing how widely adopted it was in the developer tooling ecosystem. Here is a summary:

YC-backed companies were using it

Buildt (YC 23) mentioned it in their technical discussions

Most modern code editors were built on it

Cursor.sh uses it for their codebase indexing . Their approach to constructing code graphs relies heavily on tree-sitter’s capabilities!

Developer tools were standardizing on it

Aider.chat, an AI-powered terminal-based pair programmer, uses tree-sitter for their AST processing. They have an excellent write-up on building repository maps with tree-sitter

What is tree-sitter?

Tree-sitter is a parser-generator tool and an incremental parsing library. It can build a concrete syntax tree for a source file and efficiently update the syntax tree as the source file is edited. Tree-sitter aims to be the following:

- General enough to parse any programming language

- Fast enough to parse on every keystroke

- Robust enough to provide useful results even with syntax errors

- Dependency-free with a pure C runtime library

It’s used in code editors like Atom, VSCode for features like syntax highlighting and code-folding. Apparently, the neovim people are also treesitter fanatics. The key feature is incremental parsing: it enables efficient updates to be made to the syntax tree as code changes, making it perfect for IDE features like syntax highlighting and auto-indentation.

While exploring code editor internals, we found that they typically use AST libraries + LSP (Language Server Protocol). Though LSIF indexes (LSP’s knowledge format) are an alternative for code embedding, these are skipped in CodeQA due to the complexity of multi-language support.

If you’re curious to learn more, see the tree-sitter explainer video .

Diving into the syntax with tree-sitter

The simplest way to get started is with the tree_sitter_languages module. It comes with pre-built parsers for all supported programming languages.

pip install tree-sitter-languagesYou can try playing on tree-sitter playground .

Extracting methods and classes (or arbitrary code symbols) from AST

You can find the code for this section in tutorial/sample_one_traversal.py .

Let’s look at the tree-sitter’s AST for the following code:

class Rectangle:

def __init__(self, width, height):

self.width = width

self.height = height

def calculate_area(self):

"""Calculate the area of the rectangle."""

return self.width * self.height

my_rectangle = Rectangle(5, 3)

area = my_rectangle.calculate_area()Tree-sitter’s AST for the above code (simplified):

module [0, 0] - [12, 0]

class_definition [0, 0] - [7, 39] # Rectangle

name: identifier [0, 6] - [0, 15]

body: block [1, 4] - [7, 39]

function_definition [1, 4] - [3, 28] # __init__

name: identifier [1, 8] - [1, 16]

parameters: parameters [1, 16] - [1, 37]

// ... parameter details ...

body: block [2, 8] - [3, 28]

// ... constructor implementation ...

function_definition [5, 4] - [7, 39] # calculate_area

name: identifier [5, 8] - [5, 22]

parameters: parameters [5, 22] - [5, 28]

// ... parameter details ...

body: block [6, 8] - [7, 39]

// ... method implementation ...

expression_statement [9, 0] - [9, 30] # my_rectangle = Rectangle(5, 3)

assignment

left: identifier # my_rectangle

right: call

function: identifier # Rectangle

arguments: argument_list

integer # 5

integer # 3

expression_statement [10, 0] - [10, 36] # area = my_rectangle.calculate_area()

assignment

left: identifier # area

right: call

function: attribute

object: identifier # my_rectangle

attribute: identifier # calculate_area

arguments: argument_list # ()Using recursive tree traversal to extract methods and classes

Reading the code from a file and parsing it into an AST is done as per the following snippet:

from tree_sitter_languages import get_parser

# Initialize parser and read code

parser = get_parser("python")

code = """

class Rectangle:

def __init__(self, width, height):

self.width = width

self.height = height

def calculate_area(self):

\"\"\"Calculate the area of the rectangle.\"\"\"

return self.width * self.height

my_rectangle = Rectangle(5, 3)

area = my_rectangle.calculate_area()

"""

# Parse into AST

tree = parser.parse(bytes(code, "utf8"))We traverse the AST recursively and look for node types that we want to extract.

- Each node has a type like

class_definitionorfunction_definition(and many more likeexpression_statement,assignment,identifier, etc.). The node types can vary with language e.g For Java, method is method_declaration, for Rust it’s function_item, javascript method_definition etc. - We can use the

child_by_field_namemethod to get the child node with a specific field name. - We can get the text of the node using the

textattribute. Text content is stored in bytes so we need to decode it. - Nodes form a tree like structure and we can access children using

node.children

# Extract classes and methods from AST

def extract_classes_and_methods(node):

results = {

'classes': [],

'methods': []

}

def traverse_tree(node):

# Extract class definitions

if node.type == "class_definition":

class_name = node.child_by_field_name("name").text.decode('utf8')

class_code = node.text.decode('utf8') # Gets entire source code for the class

results['classes'].append({

'name': class_name,

'code': class_code

})

# Extract method definitions

elif node.type == "function_definition":

method_name = node.child_by_field_name("name").text.decode('utf8')

method_code = node.text.decode('utf8') # Gets entire source code for the method

results['methods'].append({

'name': method_name,

'code': method_code

})

# Recursively traverse children

for child in node.children:

traverse_tree(child)

traverse_tree(node)

return results

# Use the extraction function

extracted = extract_classes_and_methods(tree.root_node)

# Print results

for class_info in extracted['classes']:

print(f"\nFound class {class_info['name']}:")

print(class_info['code'])

for method_info in extracted['methods']:

print(f"\nFound method {method_info['name']}:")

print(method_info['code'])Using tree-sitter Queries

Below is a snippet showing how to define queries and use them to extract classes and methods. See the full tutorial here .

class_query = language.query("""

(class_definition

name: (identifier) @class.name

) @class.def

""")

# Query for function (method) definitions, capturing the name and definition

method_query = language.query("""

(function_definition

name: (identifier) @method.name

) @method.def

""")

def extract_classes_and_methods(root_node):

results = {

'classes': [],

'methods': []

}

# Extract classes

for match in class_query.matches(root_node):

captures = {name: node for node, name in match.captures}

class_name = captures['class.name'].text.decode('utf8')

class_code = captures['class.def'].text.decode('utf8')

results['classes'].append({

'name': class_name,

'code': class_code

})

# Extract methods

for match in method_query.matches(root_node):

captures = {name: node for node, name in match.captures}

method_name = captures['method.name'].text.decode('utf8')

method_code = captures['method.def'].text.decode('utf8')

results['methods'].append({

'name': method_name,

'code': method_code

})

return resultsYou can read more about tree-sitter queries and tagged captures if you’d like to go deeper!

Queries are defined as follows:

class_query = language.query("""

(class_definition

name: (identifier) @class.name

body: (block) @class.body

) @class.def

""")Queries

In tree-sitter, queries are patterns that match specific syntactic structures within the abstract syntax tree (AST) of your code. They allow you to search for language constructs, such as class definitions or function declarations, by specifying the hierarchical arrangement of nodes that represent these constructs.

Tags, or captures

These are labels assigned to particular nodes within your query patterns using the @ symbol. By tagging nodes, you can extract specific parts of the matched patterns for further analysis or processing, such as names, bodies, or entire definitions.

In the code snippet above, the class_query is designed to match class_definition nodes in Python code and capture key components:

@class.name: Captures theidentifiernode that represents the class name.@class.body: Captures theblocknode that contains the body of the class.@class.def: Captures the entireclass_definitionnode.

Using this query, you can extract detailed information about each class in the code, such as the class name and its contents, which is useful for tasks like code analysis, refactoring, or documentation generation.

You can see projects storing the queries as .scm files often in projects like

aider

and

locify

.

The implementation of CodeQA for this blog post is similar, and you can check the file treesitter.py for more details. You can see how queries were defined for different languages, too.

Codebase wide references

For codebase wide references, we mainly find the function calls and class instantiations/object creation. The code from preprocessing.py looks like this:

def find_references(file_list, class_names, method_names):

references = {'class': defaultdict(list), 'method': defaultdict(list)}

files_by_language = defaultdict(list)

# Convert names to sets for O(1) lookup

class_names = set(class_names)

method_names = set(method_names)

for file_path, language in file_list:

files_by_language[language].append(file_path)

for language, files in files_by_language.items():

treesitter_parser = Treesitter.create_treesitter(language)

for file_path in files:

with open(file_path, "r", encoding="utf-8") as file:

code = file.read()

file_bytes = code.encode()

tree = treesitter_parser.parser.parse(file_bytes)

# Single pass through the AST

stack = [(tree.root_node, None)]

while stack:

node, parent = stack.pop()

# Check for identifiers

if node.type == 'identifier':

name = node.text.decode()

# Check if it's a class reference

if name in class_names and parent and parent.type in ['type', 'class_type', 'object_creation_expression']:

references['class'][name].append({

"file": file_path,

"line": node.start_point[0] + 1,

"column": node.start_point[1] + 1,

"text": parent.text.decode()

})

# Check if it's a method reference

if name in method_names and parent and parent.type in ['call_expression', 'method_invocation']:

references['method'][name].append({

"file": file_path,

"line": node.start_point[0] + 1,

"column": node.start_point[1] + 1,

"text": parent.text.decode()

})

# Add children to stack with their parent

stack.extend((child, node) for child in node.children)

return referencesIt’s a stack-based tree traversal to find the references. CodeQA takes a simpler approach here rather than using queries/tags. If the identifier’s name matches a known class name and its parent node type indicates class usage (e.g., type annotation, object creation), it’s recorded as a class reference. The same is true for methods.

Conclusions

In this post, we discussed how to go from a naive semantic code search solution to a more elaborate,syntax-level chunking strategy with tree-sitter. We’re almost done with preprocessing! In Part 2 , we’ll see how to embed, some tricks to improve embedding search and then some post-processing techniques.

References

References are listed in the order they appeared in the post:

- codeQA Github Link

- Language models are few shot learners

- In-Context Learning with Long-Context Models: An In-Depth Exploration Twitter thread

- An Intuitive Introduction to Text Embeddings (Stack Overflow blog)

- Chunking tutorial (FullStackRetrieval)

- OpenAI Web QA Embeddings Tutorial

- Hrishi’s three part series on RAG - Part 1

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey

- OpenAI Cookbook - Code search using embeddings

- Buildt (YC 23) Hacker News Comment

- Aman Sanger’s Twitter thread on codebase indexing

- Building a better repository map with tree sitter - Aiderchat

- Tree-sitter Github

- Tree-sitter Playground

- Tree-sitter explained video

- treesitter-implementations.py Github Link

- tree-sitter.py Github Link

- preprocessing.py Github Link